By Ryan M. Jones

It was summer. 1993. I was 7 years old living in Hoover Alabama, a suburb of the most segregated city in America in 1963, “Bombingham” as it was called. My mother subscribed me to the Scholastic Book club when she realized I enjoyed going to the local public library. As I scanned for a book to read, she suggested that I get a book on the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. I knew who he was. I knew there was a holiday observed in his honor. I knew he had a dream. In my hometown of Memphis Tennessee, I knew there was a museum built at the hotel that some white man shot and killed him. She told me that he helped change the world. I agreed with my mother’s suggestion. A Picture Book of Martin Luther King Jr. by David Adler arrived a few weeks later. As I had done previously with my other books, I ran back to the room I shared with my two brothers. While they were playing our Super Nintendo, I began reading about this young Baptist minister who engaged in protests during the times of when my parents were my age. I recall words I didn’t understand; civil disobedience, nonviolent resistance, Nobel Peace Prize, and then assassination. Although I had visited the National Civil Rights Museum two years earlier and now the place of my employment, it was the page towards the back of the book that I became numb and devastated. After sitting on my bed developing tears in my eyes, I ran into the kitchen where my parents were preparing dinner and wrapped my arms around my mother. As I dropped the book on the floor, I cried and continued to ask her “Why did that man shoot Dr. King? Why?” She sat me on her lap and told me “Ryan, Dr. King was a good man. He and others fought and gave their lives so America could be a better place for all of its people. But, there are some people who didn’t like Dr. King because of the color of his skin.” I understood but I didn’t. As I got older, living in the south and learning the true narrative of people of color, a narrative that has not always been taught in the most considerate and respectful way, it began to mold me into who I am today. One of my teachers in the 4th grade forced me and my other classmates to build a Southern plantation for a project and be tested on “Gone with the Wind”. The first impressions to an innocent mind can have an everlasting effect. These reflections I share with you on the commemoration of one of the greatest tragedies in our history is personal and a spiritual journey.

As I had done previously with my other books, I ran back to the room I shared with my two brothers. While they were playing our Super Nintendo, I began reading about this young Baptist minister who engaged in protests during the times of when my parents were my age. I recall words I didn’t understand; civil disobedience, nonviolent resistance, Nobel Peace Prize, and then assassination. Although I had visited the National Civil Rights Museum two years earlier and now the place of my employment, it was the page towards the back of the book that I became numb and devastated. After sitting on my bed developing tears in my eyes, I ran into the kitchen where my parents were preparing dinner and wrapped my arms around my mother. As I dropped the book on the floor, I cried and continued to ask her “Why did that man shoot Dr. King? Why?” She sat me on her lap and told me “Ryan, Dr. King was a good man. He and others fought and gave their lives so America could be a better place for all of its people. But, there are some people who didn’t like Dr. King because of the color of his skin.” I understood but I didn’t. As I got older, living in the south and learning the true narrative of people of color, a narrative that has not always been taught in the most considerate and respectful way, it began to mold me into who I am today. One of my teachers in the 4th grade forced me and my other classmates to build a Southern plantation for a project and be tested on “Gone with the Wind”. The first impressions to an innocent mind can have an everlasting effect. These reflections I share with you on the commemoration of one of the greatest tragedies in our history is personal and a spiritual journey.

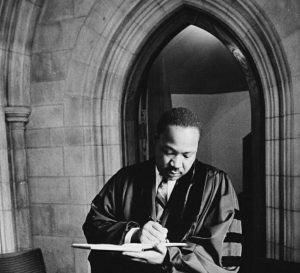

Once I realized I wasn’t going to be the next Stephen Curry or DJ Jazzy Jeff, I really began to become fascinated with Dr. King, his writings, his speeches, his personal life, and of course his mysterious assassination. From Montgomery to Selma, from Letter from a Birmingham Jail to when he publicly opposed the Vietnam War. It wasn’t until I took an upper division history course at the University of Tennessee-Martin in 2007 by one of my most influential professors and mentors Dr. David Barber, I learned that Dr. King was not the “I Have a Dream” man that we observe every third Monday in January. Reading the Fire Next Time, Soul On Ice, and The Souls of Black Folks all in one semester, I again began to evolve. I began to learn the differences between printed history and researched history. Fact vs. Myth. Dr. King indeed was a radical just as Malcolm, Stokely, Huey, and Fred Hampton had been. After Selma, his life would become exhausting, riddled with stress, and somewhat pressured by the new Black Power movement led by young and hungry Black militants who were no longer willing to use nonviolent resistance. The world was changing. David Ruffin and the Temptations took the process conks out of their hair and wore it natural. Muhammad Ali formed the seed that Colin Kaepernick would flourish from on Sunday mornings. Dr. King left the vitriol racism in the Jim Crow South and attempted to apply his tactics in the north such as Chicago. It was there he realized racial discrimination was not a southern thing, it was an American thing. He was bewildered at how the overwhelming amounts of poverty affected Americans across the country. He was perplexed at the reality of the United States government spending billions of dollars on military defense when the citizens of this country were well below the poverty line. As he had done for jobs and freedom during the March on Washington on August 28, 1963, he planned a Poor People’s Campaign for the nation’s capital as well. Only this time, he planned to have 500,000 Americans build tents and force the government to close tax loopholes and helps its citizens domestically. This, unfortunately, is what likely cost him his life. Dr. King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference were in the middle of planning the Poor People’s Campaign, when two unsung men were killed in the back of a garbage truck on a rainy afternoon in the city I was born, on the banks of the Mississippi, the city in which the “Dream” would be killed.

As he had done for jobs and freedom during the March on Washington on August 28, 1963, he planned a Poor People’s Campaign for the nation’s capital as well. Only this time, he planned to have 500,000 Americans build tents and force the government to close tax loopholes and helps its citizens domestically. This, unfortunately, is what likely cost him his life. Dr. King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference were in the middle of planning the Poor People’s Campaign, when two unsung men were killed in the back of a garbage truck on a rainy afternoon in the city I was born, on the banks of the Mississippi, the city in which the “Dream” would be killed.

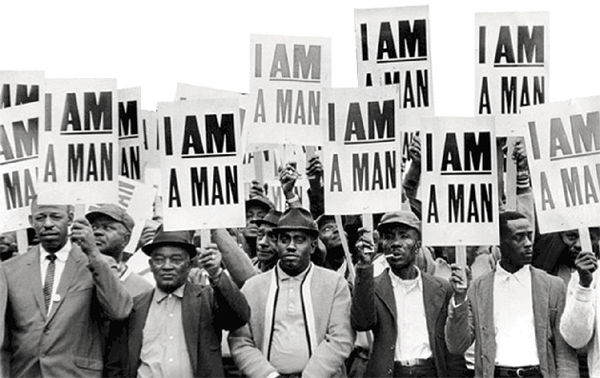

A few weeks after I cried at the assassination photograph in my Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. children’s book, my father took my brother’s and me to Blockbuster Video. While my brothers each picked the video game of their choice and I chose Burt Reynolds Cop and a Half, my dad chose a documentary titled At the River I Stand. He suggested that I watch this film with him once we got home. This documentary told the story of why Dr. King came to Memphis and eventually lost his life at the Lorraine Motel. It was a specific yet grisly story that still horrifies me to this current day. Thursday, February 1, 1968. The day of the spark in which Dr. King would come to Memphis and senselessly lose his life two months later. In East Memphis, two men, Robert Walker Jr. and Echol Cole had been Memphis sanitation workers for a few months. That Thursday was a steady hard rain in Memphis. As the crew began to return to their dump headquarters on Shelby Drive, Walker and Cole got into the back of the truck to shelter themselves. After a malfunction in the wiring, the trash compactor triggered by accident. Mr. Cole was further in the truck than Robert Walker and stuck out his hand to be pulled out. Robert Walker likely could have escaped but both men locked hands with each other and Walker was pulled in and both were crushed to death. While the Memphis press all but ignored the tragic accident, it welcomed the birth of Elvis Presley’s daughter Lisa Marie into the world. Because of the men’s death, Memphis sanitation workers formally went on strike against the city. The Reverend James Lawson would invite Dr. King to give a speech on behalf of the strikers. He would come and receive a warm and open reception from Memphis on March 18, 1968. So much that he volunteered to return to Memphis ten days later to march. When he arrived back on the 28th, there was a restless crowd awaiting him to join the marchers at the front.

This documentary told the story of why Dr. King came to Memphis and eventually lost his life at the Lorraine Motel. It was a specific yet grisly story that still horrifies me to this current day. Thursday, February 1, 1968. The day of the spark in which Dr. King would come to Memphis and senselessly lose his life two months later. In East Memphis, two men, Robert Walker Jr. and Echol Cole had been Memphis sanitation workers for a few months. That Thursday was a steady hard rain in Memphis. As the crew began to return to their dump headquarters on Shelby Drive, Walker and Cole got into the back of the truck to shelter themselves. After a malfunction in the wiring, the trash compactor triggered by accident. Mr. Cole was further in the truck than Robert Walker and stuck out his hand to be pulled out. Robert Walker likely could have escaped but both men locked hands with each other and Walker was pulled in and both were crushed to death. While the Memphis press all but ignored the tragic accident, it welcomed the birth of Elvis Presley’s daughter Lisa Marie into the world. Because of the men’s death, Memphis sanitation workers formally went on strike against the city. The Reverend James Lawson would invite Dr. King to give a speech on behalf of the strikers. He would come and receive a warm and open reception from Memphis on March 18, 1968. So much that he volunteered to return to Memphis ten days later to march. When he arrived back on the 28th, there was a restless crowd awaiting him to join the marchers at the front.  When the march turned on Main Street, there was looting at the back of the march. As the violence got worse, Dr. King was forced to leave the march that he had not organized, but would later be blamed for.

When the march turned on Main Street, there was looting at the back of the march. As the violence got worse, Dr. King was forced to leave the march that he had not organized, but would later be blamed for.  This was critical for him because he was due in Washington in the next few weeks for the Poor People’s Campaign. The national media asserted that Dr. King had lost his magic. That if he couldn’t be successful in Memphis Tennessee, then how would he thrive in Washington D.C.? An hour after the march, another unsung martyr would lose his life. Sixteen-year-old Larry Payne, a junior at Mitchell High School marched with Dr. King that morning. After returning home briefly, he and some of his other classmates were caught in the middle of the looting. Memphis Police officer Leslie Dean Jones found Larry hiding in the South Memphis housing projects Fowler Homes and demanded he come out. According to a dozen witnesses, Larry appeared with his hands above his head. L.D. Jones shoved his shotgun into Larry’s stomach and fired point blank range. Larry’s mother, Mrs. Lizzie Payne tried to approach her son lying in a pool of blood, only to be met by her son’s murderer. Jones stuck his shotgun into her stomach, telling her to “Get back, Nigger.” Larry died on the way to the hospital. Officer Jones stated that Larry ran at him with a knife, an accusation that the same dozen witnesses disagreed with. Nevertheless, L.D. Jones was not indicted or even arrested. The next day, Dr. King vowed to return to Memphis to assure that he could still lead a nonviolent campaign, as he had done in Montgomery, Birmingham, and Selma. He would return on April 3, 1968.

This was critical for him because he was due in Washington in the next few weeks for the Poor People’s Campaign. The national media asserted that Dr. King had lost his magic. That if he couldn’t be successful in Memphis Tennessee, then how would he thrive in Washington D.C.? An hour after the march, another unsung martyr would lose his life. Sixteen-year-old Larry Payne, a junior at Mitchell High School marched with Dr. King that morning. After returning home briefly, he and some of his other classmates were caught in the middle of the looting. Memphis Police officer Leslie Dean Jones found Larry hiding in the South Memphis housing projects Fowler Homes and demanded he come out. According to a dozen witnesses, Larry appeared with his hands above his head. L.D. Jones shoved his shotgun into Larry’s stomach and fired point blank range. Larry’s mother, Mrs. Lizzie Payne tried to approach her son lying in a pool of blood, only to be met by her son’s murderer. Jones stuck his shotgun into her stomach, telling her to “Get back, Nigger.” Larry died on the way to the hospital. Officer Jones stated that Larry ran at him with a knife, an accusation that the same dozen witnesses disagreed with. Nevertheless, L.D. Jones was not indicted or even arrested. The next day, Dr. King vowed to return to Memphis to assure that he could still lead a nonviolent campaign, as he had done in Montgomery, Birmingham, and Selma. He would return on April 3, 1968.

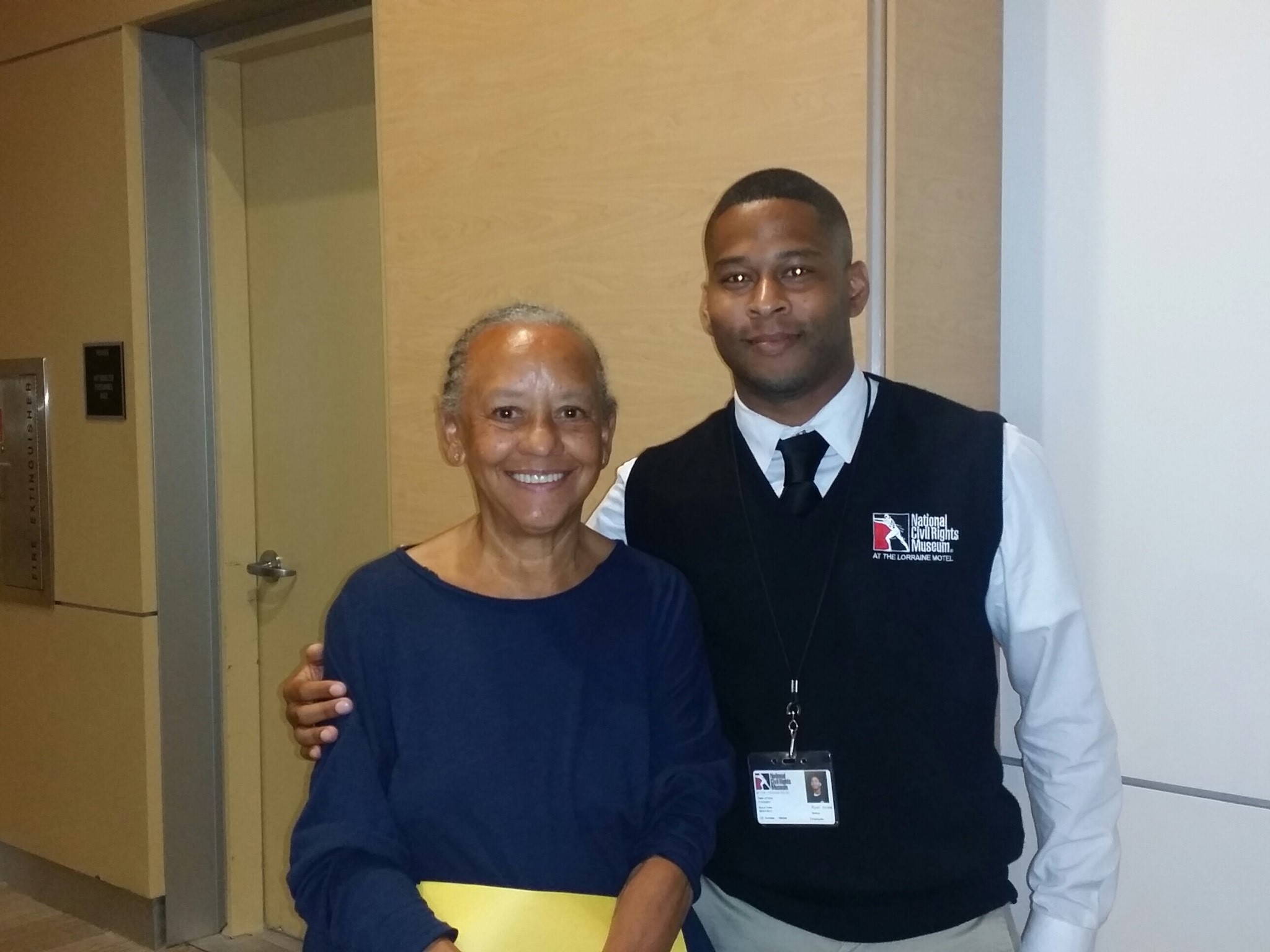

Since 2011, I’ve had the privilege of working at the National Civil Rights Museum, the site of Dr. King’s assassination. Working at this empowering institution has given me the humble opportunity to speak to all walks of life that our exhibitions interpret. While I’ve met some incredible activists, athletes, and other celebrities, the most challenging was when Dr. King’s youngest child, the Reverend Dr. Bernice King entered the museum.

I always had a great admiration for her and her parents and how she has preserved her father’s legacy. But I questioned myself on telling her a history that she already knew… AT the place of her father’s tragic death. It was by far my most humbling experience of my life standing in the spot on the second floor of the balcony of the Lorraine Motel with her gazing across the street into the area a loud rifle shot was fired from. I felt grief, anger, and sorrow. I began to tell her of the moment Dr. King arrived back in Memphis on April 3, 1968 on flight 381 on Eastern Airlines. Before arriving however, there was a bomb threat that delayed him by an hour. After arriving in Memphis, he was transported to the Lorraine Motel, a black-owned and prestigious hotel that catered to legends such as Sam Cooke, Jackie Robinson, Aretha Franklin, and Lena Horne.

I always had a great admiration for her and her parents and how she has preserved her father’s legacy. But I questioned myself on telling her a history that she already knew… AT the place of her father’s tragic death. It was by far my most humbling experience of my life standing in the spot on the second floor of the balcony of the Lorraine Motel with her gazing across the street into the area a loud rifle shot was fired from. I felt grief, anger, and sorrow. I began to tell her of the moment Dr. King arrived back in Memphis on April 3, 1968 on flight 381 on Eastern Airlines. Before arriving however, there was a bomb threat that delayed him by an hour. After arriving in Memphis, he was transported to the Lorraine Motel, a black-owned and prestigious hotel that catered to legends such as Sam Cooke, Jackie Robinson, Aretha Franklin, and Lena Horne. The Lorraine was owned by power couple Walter and Loree Bailey, who renovated the hotel and motel several times during the peaking years of the Civil Rights Movement. For $13 a night, African-Americans could relax and feel safe at the Lorraine.

The Lorraine was owned by power couple Walter and Loree Bailey, who renovated the hotel and motel several times during the peaking years of the Civil Rights Movement. For $13 a night, African-Americans could relax and feel safe at the Lorraine. Of course, Dr. King, on his three visits to the Lorraine, would never be charged for his stay. As he met with his staff and local Memphis leaders including a young Black Power splinter group The Invaders, King began to feel ill. He suffered from laryngitis and developed flu-like symptoms. There was also tornado warnings in the great Memphis area which he felt would affect the attendance at that night’s rally at the Mason Temple. He requested that Reverend Ralph Abernathy, later UN Ambassador Andrew Young and a young Reverend Jesse Jackson attend in his place. He would catch up on some rest. When the three men arrived, they were stunned to see 3,000 people standing up as they walked in. Then the ovation grew quiet as they noticed Dr. King was not with them. Abernathy leaned to Andrew Young and laughed “this is Martin’s crowd. We have to get him here immediately.” He rushed to the nearest phone and called room 306 at the Lorraine Motel and urged Dr. King to get to the Temple quick. “The news cameras are all here. This will be shown nationally.” Dr. King arrived in 25 minutes. Abernathy delivered an unusually long biography of his oldest friend before Dr. King reached the podium. He had no notes. In an ode to Hip Hop, he planned to “freestyle” his remarks for the next forty minutes. He spoke of the strike. He spoke his commitment of leading a nonviolent march in Memphis. He spoke of his determination to reach Washington. He then spoke of various events during his 12-year tenure in the Civil Rights Movement. The afternoon he was stabbed by a deranged woman in Harlem. The Sit-ins. Bull Connor and Birmingham. Bloody Sunday and Selma. And then it happened.

Of course, Dr. King, on his three visits to the Lorraine, would never be charged for his stay. As he met with his staff and local Memphis leaders including a young Black Power splinter group The Invaders, King began to feel ill. He suffered from laryngitis and developed flu-like symptoms. There was also tornado warnings in the great Memphis area which he felt would affect the attendance at that night’s rally at the Mason Temple. He requested that Reverend Ralph Abernathy, later UN Ambassador Andrew Young and a young Reverend Jesse Jackson attend in his place. He would catch up on some rest. When the three men arrived, they were stunned to see 3,000 people standing up as they walked in. Then the ovation grew quiet as they noticed Dr. King was not with them. Abernathy leaned to Andrew Young and laughed “this is Martin’s crowd. We have to get him here immediately.” He rushed to the nearest phone and called room 306 at the Lorraine Motel and urged Dr. King to get to the Temple quick. “The news cameras are all here. This will be shown nationally.” Dr. King arrived in 25 minutes. Abernathy delivered an unusually long biography of his oldest friend before Dr. King reached the podium. He had no notes. In an ode to Hip Hop, he planned to “freestyle” his remarks for the next forty minutes. He spoke of the strike. He spoke his commitment of leading a nonviolent march in Memphis. He spoke of his determination to reach Washington. He then spoke of various events during his 12-year tenure in the Civil Rights Movement. The afternoon he was stabbed by a deranged woman in Harlem. The Sit-ins. Bull Connor and Birmingham. Bloody Sunday and Selma. And then it happened. As the shutters of the church were slamming because of the tornado winds, he gazed into his audience and said “I don’t know what will happen now. We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it really doesn’t matter with me now, because I’ve been to the mountaintop. And I don’t mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land! And so I’m happy, tonight. I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man!

As the shutters of the church were slamming because of the tornado winds, he gazed into his audience and said “I don’t know what will happen now. We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it really doesn’t matter with me now, because I’ve been to the mountaintop. And I don’t mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land! And so I’m happy, tonight. I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man!

Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord!” He collapsed into the arms of his staff. The time was 10:30 PM. Dr. King had just delivered his final address to the world.

Every morning as I begin my day, I walk through the museum to remind myself that not only is this is my job. But this my life and purpose. The men, women, and children. Black and White. The courage and sacrifices. So that people like myself and others can keep this rich history alive. That the future generations know that we are not makers of history, but that we are made by history.

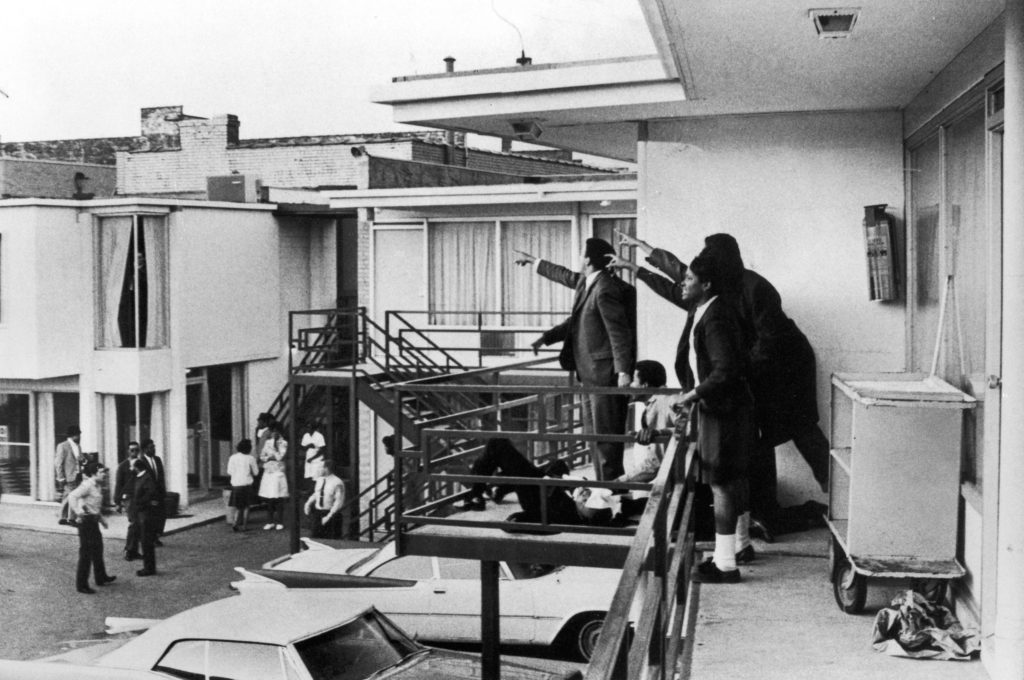

And as I approach the room that Dr. King was taken from us, I remember that he was one man. A son, father, husband, who was full of vulnerability like all of us. The day after he delivered the most emotional, yet inspiring speech in my life, Dr. King was in the most joyous mood that he had been in weeks. When Andrew Young returned from Federal court to have an injunction lifted, he threw him onto a bed in Room 202 of the Lorraine and began child-like pillow fight. After wrestling themselves into an appetite, Dr. King went upstairs around 5:30 PM to his room to get dressed for a soul food dinner at Memphis minister’s home Samuel “Billy” Kyles. Dr. King reappeared on the balcony at 5:55 PM. He spoke to Jesse Jackson, whom he scolded the weekend before at an SCLC meeting in Atlanta. He told Jesse he wanted him to come to dinner with him and that he needed to put on a necktie. Jesse called back up to say “Doc, a prerequisite for dinner is an appetite and I have that.” The men laughed. Jesse introduced Dr. King to Ben Branch, a saxophonist who was going to play that night after dinner. Dr. King knew him already. He personally requested Mr. Branch to play “Precious Lord”, his favorite spiritual. “Play it real pretty.” Dr. King’s chauffeur called up and told him to grab his topcoat. Before Dr. King could reply, he was lifted upward off the ground and thrown back violently to the floor on the balcony. Everyone who was in the courtyard thought it was a car backfiring. Then they looked and saw Dr. King’s shoes dangling on the balcony and rushed to his aide. There was a large and mortal wound in the right side of his lower jaw and neck. Ralph Abernathy thought Dr. King recognized him for a few seconds, but he never spoke a word. Almost immediately, the Memphis Police Department was running toward the Lorraine balcony. In that instant, South African photographer Joseph Louw took the photo of Dr. King’s aides pointing west in the direction of where they felt the shot came from.  After being taken from the balcony to St. Joseph’s Hospital, now St. Jude, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was pronounced dead at 7:05 PM central standard time. His death wasn’t the only to haunt the Lorraine. Mrs. Loree Bailey, the co-owner of the motel began shaking when she saw Dr. King lying on the balcony. Hours later, a blood vessel popped in her brain and she would fall into a coma before dying five days later, the day Dr. King was eulogized in Atlanta.

After being taken from the balcony to St. Joseph’s Hospital, now St. Jude, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was pronounced dead at 7:05 PM central standard time. His death wasn’t the only to haunt the Lorraine. Mrs. Loree Bailey, the co-owner of the motel began shaking when she saw Dr. King lying on the balcony. Hours later, a blood vessel popped in her brain and she would fall into a coma before dying five days later, the day Dr. King was eulogized in Atlanta.

Riots and urban uprisings burned across the United States. The apostle of nonviolence was gone. Who could have done such a thing? James Earl Ray, a petty criminal with a 2nd-grade education and at best a poor shot with a rifle, with a scope that still has never been sighted? From a window where no eyewitness picked him out of a lineup?  Could James Earl Ray changed Dr. King’s room at the Lorraine Motel on April 3? Could he have ordered the Memphis Public Works have obscuring bushes and grass removed in the middle of the night after the assassination, where several eyewitnesses saw gun smoke and a man moving rather quickly when the shot was fired? Could Ray have successfully removed three African-American officers from their post at the Memphis Fire Station adjacent to the Lorraine Motel? Could James Earl Ray conveniently left his bundle with the alleged murder weapon just 300 feet from the scene of the crime and leave Memphis undetected and arrive in Atlanta, Toronto, and London, with 5 separate aliases of men that looked almost identical to him? 50 years later, these lingering questions still remain. 50 years later, we still don’t have concise answers. While I believe the extensive plot to kill Dr. King goes much further and complex than the likes of James Earl Ray, we must still consider the fear and threat Dr. King caused at the time of his death. Just two months later, Senator Robert F. Kennedy suffered the same fate. The very same principles that Dr. King stood for, men and women are still being ridiculed today. Racism. Poverty. Militarism. Those who hide their prejudiced ways for their patriotism and those who don’t have a decent living wage to take care of their families. Is that why he was murdered? Dr. King died the most hated man on the planet. Today, he is one of the most glorified. Did it take him to be shot down on a balcony of a hotel in Memphis so African-American sanitation workers could live better lives? Is that a dream or a nightmare?

Could James Earl Ray changed Dr. King’s room at the Lorraine Motel on April 3? Could he have ordered the Memphis Public Works have obscuring bushes and grass removed in the middle of the night after the assassination, where several eyewitnesses saw gun smoke and a man moving rather quickly when the shot was fired? Could Ray have successfully removed three African-American officers from their post at the Memphis Fire Station adjacent to the Lorraine Motel? Could James Earl Ray conveniently left his bundle with the alleged murder weapon just 300 feet from the scene of the crime and leave Memphis undetected and arrive in Atlanta, Toronto, and London, with 5 separate aliases of men that looked almost identical to him? 50 years later, these lingering questions still remain. 50 years later, we still don’t have concise answers. While I believe the extensive plot to kill Dr. King goes much further and complex than the likes of James Earl Ray, we must still consider the fear and threat Dr. King caused at the time of his death. Just two months later, Senator Robert F. Kennedy suffered the same fate. The very same principles that Dr. King stood for, men and women are still being ridiculed today. Racism. Poverty. Militarism. Those who hide their prejudiced ways for their patriotism and those who don’t have a decent living wage to take care of their families. Is that why he was murdered? Dr. King died the most hated man on the planet. Today, he is one of the most glorified. Did it take him to be shot down on a balcony of a hotel in Memphis so African-American sanitation workers could live better lives? Is that a dream or a nightmare?