By David Jordan Jr

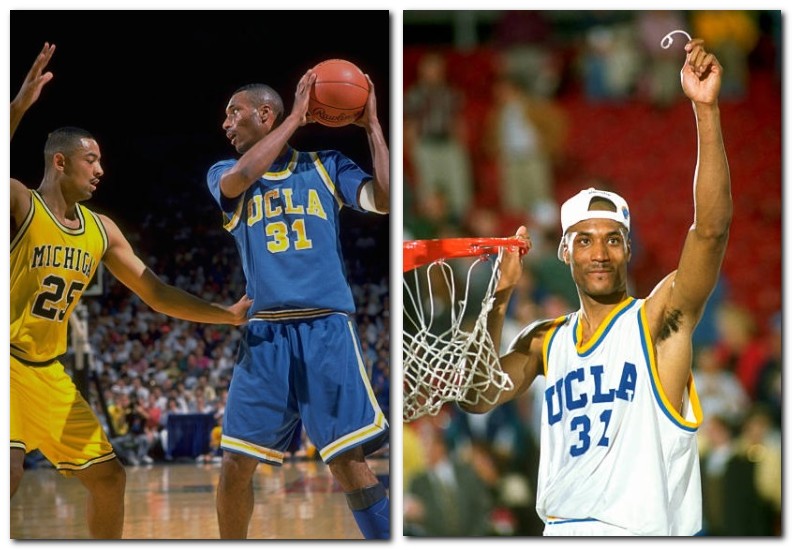

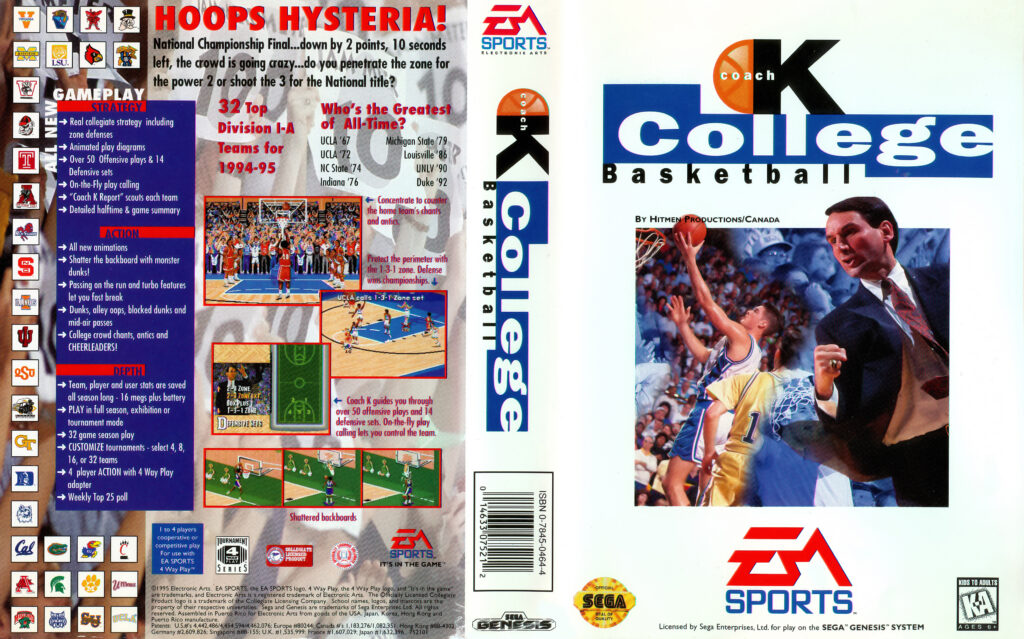

Recently the NCAA passed a rule allowing collegiate student-athletes to make money off of their name, imaging, and likeness while being student-athletes at their respective universities. This ruling comes after years of fighting from previous student-athletes that sought to obtain a portion of the billions of dollars of revenue generated at the universities at which they’ve played sports. NCAA athletics generated $995.9 million dollars in 2016 and in 2019 the revenue was $18.9 billion dollars. The bulk of this money came from ticket sales, broadcast rights, and NCAA and conference distributions (conference tournament revenue, and other partnership deals. The large amount of revenue isn’t new; it’s been consistent and steadily growing over the years with the advances in technology, sports marketing, global expansion and representation of NCAA athletics and partnerships with many different athletic shoe and apparel companies. In 2009 former UCLA basketball star and NBA Lottery Pick (1995 NBA Draft, 9th Pick) Ed O’Bannon filed a lawsuit against the NCAA and the Collegiate Licensing Company. O’Bannon’s likeness had been used not only during his college basketball career on video games (Coach K’s College Basketball, Sega Genesis, NCAA Basketball, and March Madness after his collegiate career) but also on jerseys that were replicas of the game jerseys he played in during his career at UCLA.

O’Bannon’s likeness had been used not only during his college basketball career on video games (Coach K’s College Basketball, Sega Genesis, NCAA Basketball, and March Madness after his collegiate career) but also on jerseys that were replicas of the game jerseys he played in during his career at UCLA.

Upon filing the suit, former University of Cincinnati Basketball legend Oscar Robertson and University of San Francisco Basketball legend Bill Russell joined the suit as plaintiffs. Previous to O’Bannon’s suit the most notable discussions stemming around college athletes and financial compensation were born with the game-changing freshmen that played college basketball in Ann Arbor, Michigan; The Fab Five.

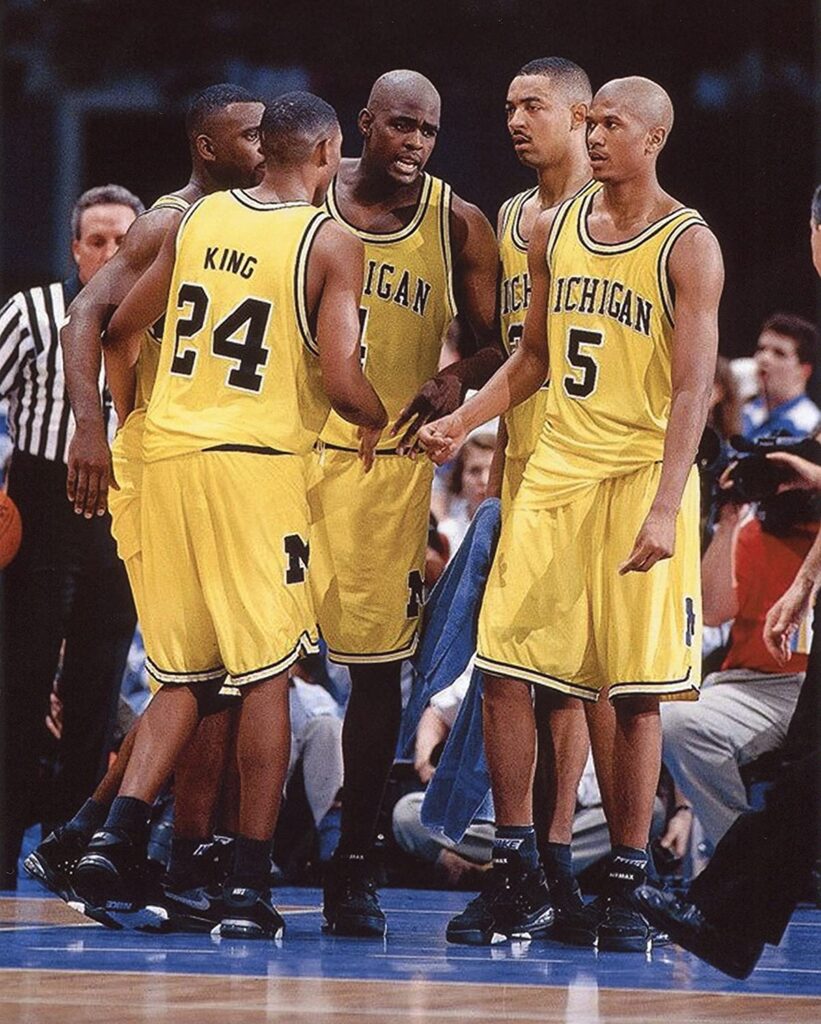

Upon filing the suit, former University of Cincinnati Basketball legend Oscar Robertson and University of San Francisco Basketball legend Bill Russell joined the suit as plaintiffs. Previous to O’Bannon’s suit the most notable discussions stemming around college athletes and financial compensation were born with the game-changing freshmen that played college basketball in Ann Arbor, Michigan; The Fab Five.  Ray Jackson, Jalen Rose, Jimmy King, Chris Webber, and Juwan Howard took the world of college basketball by storm when they made their debut as freshmen at the University of Michigan in the fall of 1991.

Ray Jackson, Jalen Rose, Jimmy King, Chris Webber, and Juwan Howard took the world of college basketball by storm when they made their debut as freshmen at the University of Michigan in the fall of 1991.

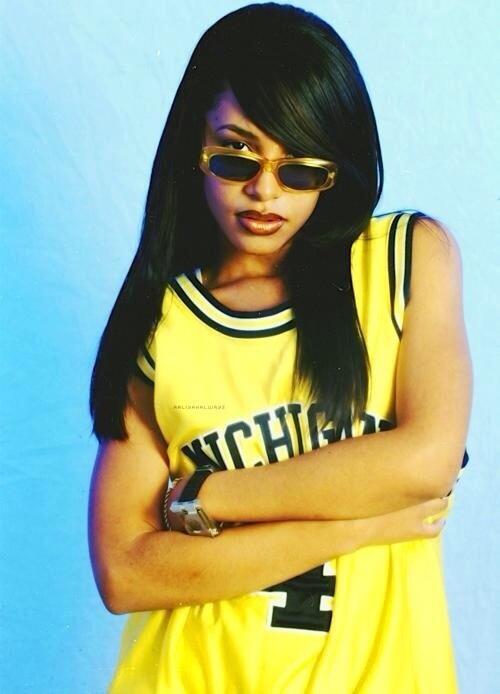

As great as they performed on the court during their years as Wolverines, they made an even greater impact upon the culture of the game of basketball worldwide. The bigger, baggy shorts, the black Nike socks, and their play in their team-issued Nike shoes cultivated the world and not only made them popular but also made the University of Michigan even more popular and made Nike products even more visible and wanted than ever before to people all over the world. This popularity was amazing as it was also during the time at which Michael Jordan (a Nike athlete) was at the peak of his career as a Nike endorser and also a global ambassador to the game of basketball. The other side of the off-court popularity was the presence of Michigan jerseys everywhere. From mainstream television, to hip hop, to everyday citizens, you could find somebody rocking any one of the Fab Five jerseys.

As great as they performed on the court during their years as Wolverines, they made an even greater impact upon the culture of the game of basketball worldwide. The bigger, baggy shorts, the black Nike socks, and their play in their team-issued Nike shoes cultivated the world and not only made them popular but also made the University of Michigan even more popular and made Nike products even more visible and wanted than ever before to people all over the world. This popularity was amazing as it was also during the time at which Michael Jordan (a Nike athlete) was at the peak of his career as a Nike endorser and also a global ambassador to the game of basketball. The other side of the off-court popularity was the presence of Michigan jerseys everywhere. From mainstream television, to hip hop, to everyday citizens, you could find somebody rocking any one of the Fab Five jerseys.

The plot twist is that the players never received a penny from all of the sales that were made by these companies because of their on-court prowess, unique style, and historical on-court performances. The University of Michigan made it to two consecutive NCAA Final Fours, led by Jalen, Jimmy, Ray, Juwan and Chris. The visibility on CBS, ESPN, NBC, ABC, and the many forms of print and video worldwide was essentially free marketing for Nike, the NCAA, and the University of Michigan. Mitch Albom’s book “Fab Five” spoke about how Chris Webber saw his Michigan jersey for sale in a window of a store, yet he could not afford to buy himself a simple dinner. The Fab Five realized their profitability and began silent protest by making some things less visible (shirts flipped inside out) and by gaining a true understanding of the business of basketball. University of Michigan Football legend and Heisman Trophy winner Desmond Howard was another athlete on the Ann Arbor campus that generated revenue at not only The Big House but also in the campus bookstores and Footlockers nationwide as his #21 jersey was sold and visible all across America. 2005 Heisman winner and USC Football legend Reggie Bush generated millions for the University of Southern California in addition to his jersey being sold in many different athletic stores and online in many different places. Bush received no money from these sales that were all a result of his performance on the field.

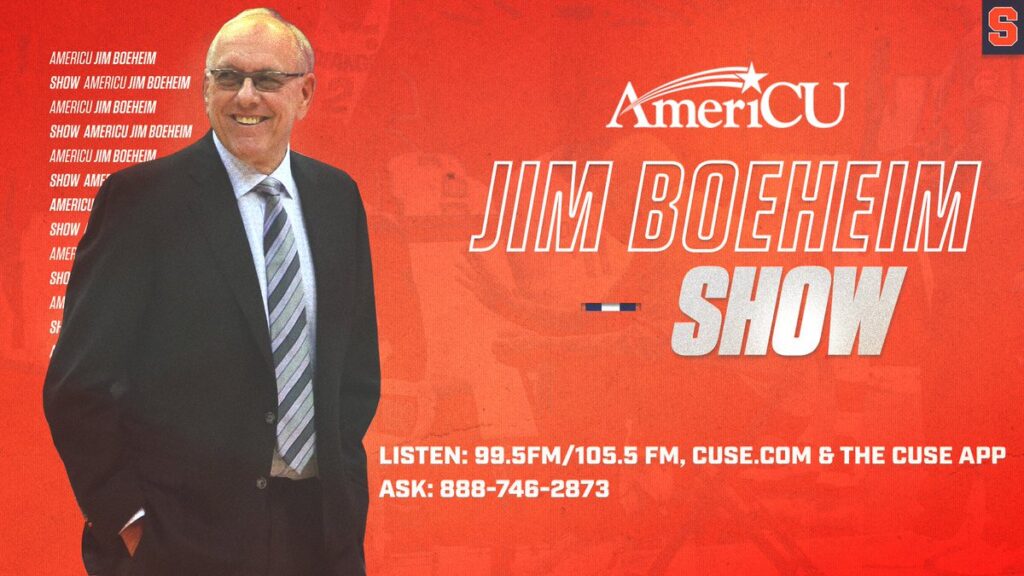

2005 Heisman winner and USC Football legend Reggie Bush generated millions for the University of Southern California in addition to his jersey being sold in many different athletic stores and online in many different places. Bush received no money from these sales that were all a result of his performance on the field. The aforementioned NCAA athletes are just a few of many that have generated billions of dollars for not only their respective schools and conferences but also for all of the major networks, shoe companies (many teams up until recently had shoe and apparel deals with Nike, Converse, Adidas, Reebok and more recently Under Armour). The biggest arguments came from those that would say “they are on a full scholarship, they do not need to make any money” but the difference between regular students and NCAA student Athletes (especially on the Division I level) is that in years past, college athletes were not allowed to have a job. As a former Division I athlete, I understand and have seen how many student-athletes that need to work, weren’t able to work in the past and they and their families struggled financially. Think about being an athlete, playing a video game in your dorm room eating noodles, chips and a bologna sandwich with your likeness (your hair cut, your jersey number, your on court/on filed skills) that is being sold at Walmart or a toy store for anywhere ranging from $49.99 to $99.99 and you get absolutely none of that money. A monopoly on student-athletes was essentially commonplace before this new ruling by the NCAA. Now the new question will be will this solve the problem of student-athletes being fairly compensated or will this create new problems where athletes will still be taken advantage of and not truly be compensated for the revenues they generate. College coaches have always been able to earn additional revenue based on winning in the forms of endorsement deals, television shows on local networks (talking about the respective sports team and players that they coach), restaurants, and even food (do you remember Finch Vanilla ice cream, a play on French Vanilly ice cream made for former Memphis State and University of Memphis basketball legend and coach Larry Finch).

The aforementioned NCAA athletes are just a few of many that have generated billions of dollars for not only their respective schools and conferences but also for all of the major networks, shoe companies (many teams up until recently had shoe and apparel deals with Nike, Converse, Adidas, Reebok and more recently Under Armour). The biggest arguments came from those that would say “they are on a full scholarship, they do not need to make any money” but the difference between regular students and NCAA student Athletes (especially on the Division I level) is that in years past, college athletes were not allowed to have a job. As a former Division I athlete, I understand and have seen how many student-athletes that need to work, weren’t able to work in the past and they and their families struggled financially. Think about being an athlete, playing a video game in your dorm room eating noodles, chips and a bologna sandwich with your likeness (your hair cut, your jersey number, your on court/on filed skills) that is being sold at Walmart or a toy store for anywhere ranging from $49.99 to $99.99 and you get absolutely none of that money. A monopoly on student-athletes was essentially commonplace before this new ruling by the NCAA. Now the new question will be will this solve the problem of student-athletes being fairly compensated or will this create new problems where athletes will still be taken advantage of and not truly be compensated for the revenues they generate. College coaches have always been able to earn additional revenue based on winning in the forms of endorsement deals, television shows on local networks (talking about the respective sports team and players that they coach), restaurants, and even food (do you remember Finch Vanilla ice cream, a play on French Vanilly ice cream made for former Memphis State and University of Memphis basketball legend and coach Larry Finch).

A bigger obstacle that may develop for the athletes as they are able to finally have an opportunity to profit off of their likeness is the availability of not only contractual deals that will provide consistent revenue, but also having people and agents in their corner that will look out for their best interests. Many agents, not all, seek to maximize their pockets, not their clients which in turn could lead to student-athletes not making or receiving the money they are actually entitled to from the revenue “sharing.” Social media and the internet have enabled student-athletes to garner recognition and marketability earlier in their athletic careers, even as early as elementary school but the ultimate decision to enable them to make money will come from the shoe companies, athletic apparel companies, clothing companies, etc. Will there be a systematic approach in place where all athletes can get endorsement deals that would be fair in conjunction with where they play? Lavar Ball, CEO of Big Baller Brand and the founder of the JBA (Junior Basketball Association) was chastised by the media severely over the last five years for saying that he would not allow his kids to be exploited by NCAA basketball.

A bigger obstacle that may develop for the athletes as they are able to finally have an opportunity to profit off of their likeness is the availability of not only contractual deals that will provide consistent revenue, but also having people and agents in their corner that will look out for their best interests. Many agents, not all, seek to maximize their pockets, not their clients which in turn could lead to student-athletes not making or receiving the money they are actually entitled to from the revenue “sharing.” Social media and the internet have enabled student-athletes to garner recognition and marketability earlier in their athletic careers, even as early as elementary school but the ultimate decision to enable them to make money will come from the shoe companies, athletic apparel companies, clothing companies, etc. Will there be a systematic approach in place where all athletes can get endorsement deals that would be fair in conjunction with where they play? Lavar Ball, CEO of Big Baller Brand and the founder of the JBA (Junior Basketball Association) was chastised by the media severely over the last five years for saying that he would not allow his kids to be exploited by NCAA basketball.  He created his own shoe company and professional league to help kids not only pursue their basketball goals but to also learn about and understand the importance of ownership in regards to personal branding, imaging, marketing, and likeness. Lavar’s three sons Lonzo Ball, LiAngelo Ball and LaMelo Ball all were heavily recruited prospects coming out of Chino Hills High School. Seeing how things could potentially play out for his sons making others money, Lavar understood the importance of maximizing self in regards to sports and finances. The youngest son, LaMelo Ball became the first-ever player to have a signature shoe as a high school student-athlete. In the five years that have passed since Lavar first spoke up about NCAA profitability and exploitation, all three of his sons have put on an NBA jersey in some capacity (Lonzo #2 Pick in the 2017 NBA Draft, LaMelo #3 pick of 2020 NBA Draft and 2020-2021 NBA Rookie Of The Year, LiAngelo G-League and Detroit Pistons Free Agent) and have been able to make money off of their own brand (Big Baller Brand) in addition to other shoe and apparel companies.

He created his own shoe company and professional league to help kids not only pursue their basketball goals but to also learn about and understand the importance of ownership in regards to personal branding, imaging, marketing, and likeness. Lavar’s three sons Lonzo Ball, LiAngelo Ball and LaMelo Ball all were heavily recruited prospects coming out of Chino Hills High School. Seeing how things could potentially play out for his sons making others money, Lavar understood the importance of maximizing self in regards to sports and finances. The youngest son, LaMelo Ball became the first-ever player to have a signature shoe as a high school student-athlete. In the five years that have passed since Lavar first spoke up about NCAA profitability and exploitation, all three of his sons have put on an NBA jersey in some capacity (Lonzo #2 Pick in the 2017 NBA Draft, LaMelo #3 pick of 2020 NBA Draft and 2020-2021 NBA Rookie Of The Year, LiAngelo G-League and Detroit Pistons Free Agent) and have been able to make money off of their own brand (Big Baller Brand) in addition to other shoe and apparel companies.  The mass exodus of high school talent to international basketball leagues to earn a paycheck in preparation for the NBA caused a restrategizing of the NBA G-Leauge to create incentive-based pay that would help in retaining the top talent in America. The NCAA also incurred revenue losses in some capacities (not majorly) as the top student-athletes were leaving school or not attending at all so that they could begin making money and not have to see their image and likeness bringing in money to other corporations without essentially any “pieces of the pie.” The new NCAA ruling which has been fought for by many college athletes from the past is indeed groundbreaking; the universal hope with the groundbreaking is that student-athletes will be able to fully benefit from their marketability and likeness in the same ways in which the NCAA, media companies and shoe/apparel companies have throughout the years.

The mass exodus of high school talent to international basketball leagues to earn a paycheck in preparation for the NBA caused a restrategizing of the NBA G-Leauge to create incentive-based pay that would help in retaining the top talent in America. The NCAA also incurred revenue losses in some capacities (not majorly) as the top student-athletes were leaving school or not attending at all so that they could begin making money and not have to see their image and likeness bringing in money to other corporations without essentially any “pieces of the pie.” The new NCAA ruling which has been fought for by many college athletes from the past is indeed groundbreaking; the universal hope with the groundbreaking is that student-athletes will be able to fully benefit from their marketability and likeness in the same ways in which the NCAA, media companies and shoe/apparel companies have throughout the years.